Wannabe Gangstar

Another view of Chi-town in Naked Lunch, with its “invisible hierarchy of decorticated wops,” (surely one of the most eloquent and intelligent and poetic slurs ever leveled at an ethnic group — not that Italian-Americans would see it like that) and “rancid magic of slot machines” (illegal slot machines were run by the Mafia in Chicago during the Burroughs Chicago period) shows that the psychic residue the city left with the writer was tied to gangsters and violence. When Burroughs first visited the mobster’s city, it was only seven years since Al Capone had been sent to prison. John Dillinger, who had been gunned down by the Chicago police in 1934 outside the Biograph Theater, gets two mentions in Naked Lunch. One of the gun-and-violence-obsessed writer’s small army of therapists over the years actually called him a “gangsterling,” a wannabe gangster. The exciting underworld appeal of a gangster-history-filled city like Chicago to a man like that is obvious. Though later in life he would come to regard mobsters as monsters, in 1969 he did write The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, a film script using the dying delirious ravings of the 20s-and-30s-era gangster as a springboard.

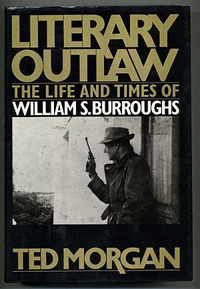

Probably inspired by the illegal activities of his new playmates from Mrs Murphy’s, Burroughs — who, as noted in Literary Outlaw, kept a gun in a sock in his closet — concocted Boy’s Own-style schemes and scams to get some cash and elevate (well, lower) him into the criminal underclass. He wanted to blow up a Brinks truck over a manhole (very Freudian!) with a bomb. Then he got the idea of holding up a Turkish bath he frequented (maybe it was the idea of all those naked men at gunpoint that got him hot). But on the fateful day he threw a few back in a bar to get Dutch courage and ended up turning up after the day’s takings had been taken away (maybe by the Brinks truck he failed to blow up — we can but hope).

You can’t win.

Just ask Jack Black.

But underneath it all, Burroughs sadly knew he was a soft wee middle class boy playing at being a hard man. As he ruefully truthfully noted decades later in the 1995 volume My Education: A Book of Dreams: “My criminal activities (minimal to be sure) were as hopelessly inept as my efforts to hold a job in an advertising agency or any other regular job.” Interesting that he equated being a criminal with work (he had no affinity for). He knew he was fated to be an Eternal Outsider, not fitting in with the seedy underworld any more than he fit in with the St. Louis WASP elites he was alienated from and hated so much. As he said in the same volume: “I have never felt close to any cause or people, so I envy from a distance of incomprehension those who speak of ‘my people.’”

(Text: Graham Rae)