Hospital

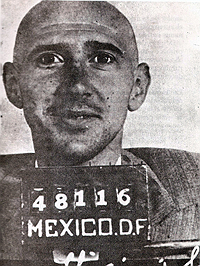

“‘Son cosas de la vida,’ as Sobera de la Flor said…” (50); incorrectly given in previous editions as “Soberba de la Flor,” the “Restored” text confirms the reference is to Higinio “El pelón” (Baldy) Sobera. Burroughs himself provides a short gloss here, in one of Naked Lunch’s many interpolated editorial parentheses: “(Sobera de la Flor was a Mexican criminal convicted of several rather pointless murders.)” In context, Burroughs’ explanatory note is mystifying, however, since these murders (and the necrophilia he attributes to the killer in this passage) appear to have little to do with the acts set in Morocco that prompt the reference in the first place — feeling like a “dirty old man” for shamelessly paying “two kids [to] screw each other.” In a first approach, we can follow the line beyond the text towards the historical occasion behind it.

On 11th March 1952, Sobera de la Flor went on a killing spree in Mexico City that left three people dead (Capt. Armando Lepe Ruiz, Hortensia López, and Pedro Galván Santoyo). Since these killings took place in the colonia Roma, exactly the district of the city where Burroughs was then living (his address on Orizaba was just a few hundred yards from the intersection of Insurgentes and Yucatán where the first murder took place), it’s very likely he would have paid attention to coverage in the Mexican newspapers. He may well also have noted that the Bald Killer ended up in the infamous Palacio Negro — where Burroughs himself had been briefly incarcerated following the shooting of Joan, just six months earlier in September 1951. In other words, there’s a very precise connection in this reference that stands in for Burroughs’ own act of deadly violence in Mexico City, and the faint ghost of Joan subtly haunts this passage.

In a second approach, we should consider the killer’s (supposed) saying, Son cosas de la vida. The phrase means something like, “that’s life” or “c’est la vie” and Burroughs offers various equivalents throughout Naked Lunch, from Doc Benway’s “Jedermann macht eine kleine Dummheit.‘ (Everyone makes a little dumbness.)” in “Ordinary Men and Women” to the variations “‘Zut alors‘ or ‘Son cosas de la vida’ or ‘Allah fucked me, the All Powerful . . .’” in “Islam Incorporated” (123). The Spanish phrase itself recurs in the “Benway” section (25), and it’s this identification with Benway that’s most significant. In “Benway,” he uses it as an expression of casual fatalism to shrug off the “Party Poops” who cut short his shameless opportunities for behavioural conditioning and sexual exploitation in Annexia. Pooping the party connects the German and Spanish expressions as formulae for bypassing morality, responsibility, and conscience, for simply getting on with life, even when that involves dealing in death.

I’m reminded of the currently ubiquitous injunction to “move on,” and it’s in this sense of not bothering to look back that Benway makes his appearance in “Hospital,” immediately after the reference to Sobera de la Flor: with a patient lying dead on his lavatory operating room table, the good doctor walks away, quipping, “Well, it’s all in the day’s work” (51). Or as Donald Rumsfeld infamously responded to the looting and murderous chaos in “liberated” Iraq: “stuff happens.”

Rumsfeld was no doubt sincere, but what about Burroughs? Do these amoral injunctions that pepper the text operate like the repeated “So it goes,” responding to each death in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five — i.e. as a moral challenge to the self-serving appeal of instant amnesia, convenient fatalism, the relegation of “stuff” to the past, business as usual? The answer perhaps lies with Christopher Marlowe. Just before Benway makes his fatal incision, he reminisces about the time he “removed a uterine tumor” with his teeth: “That was in the Upper Effendi, and besides . . .” The ellipsis must be filled by The Jew of Malta: “Thou has committed — / Fornication: but that was in another country, / And besides, the wench is dead.” (The Prof. in “Campus of Interzone University” also does some filling in: “That was in another country, gentlemen . . .” [73]) The pieces finally begin to fall into place, and to explain why in a hospital set in Morocco Burroughs should invoke, via Sobera de la Flor, Mexico — “another country,” site of another “pointless murder.” Son cosas de la vida?

(Text: Oliver Harris)

Thoughts about this section? Add a comment below or return to Naked Lunch: Section by Section.