Dunking Pound Cake

The Waldorf, Bickford’s, and the Automat

“I cut into the automat and there is Bill Gains huddled in someone else’s overcoat looking like a 1910 banker with paresis, and Old Bart, shabby and inconspicuous, dunking pound cake with his dirty fingers, shiny over the dirt.”

The words “supper” and “dinner” appear once each in Naked Lunch. “Breakfast” appears twice. “Lunch” and cognates such as “luncheon” and “lunchroom” appear ten times. In any other book, you would suspect that the author had deliberately emphasized “lunch” as a way of reinforcing his title and his theme. But in Naked Lunch? Given that Burroughs famously — but spuriously — denied any recollection of writing the book, it is difficult to imagine him giving any conscious thought to the role played by a midday meal. “They just bring so-called lunch…. A hard-boiled egg with the shell off revealing an object like I never seen it before….” His attitude toward Naked Lunch seems to have been something of the same — “like I never seen it before.”

And yet “lunch” and lunchrooms recur with the persistence of an unconscious act of repetition. William Lee and his junky brethren traverse an anonymous network of two-bit eateries. The cafe in Tangier, the restaurant (”mosaic bar and soccer scores and bullfight posters”) in Mexico, the lunch counter in New York — typically these were real places that migrated first into Burroughs’ early work and then into the more hallucinatory landscape of Naked Lunch, where they practically serve as extensions and satellites of the Composite City.

Waldorf Cafeteria, 6th Avenue, New York, 1954. The Waldorf is the light-colored building to the lower right of the picture. (Photograph from Luther Harris, Around Washington Square: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village.)

For example, a young junky who has prostituted himself to the dangerously osmotic Buyer finds himself “sitting in a Waldorf with two colleagues dunking pound cake.” Where is this Waldorf? Is it a real place? Later in Naked Lunch Burroughs writes that “The Gimp, cowboyed in the Waldorf, gives birth to a litter of rats.” Evidently this second Waldorf was a hotel in Philadelphia, since another passage specifies that “I saw the Gimp catch one in Philly.” Was the first Waldorf the same place? Was it perhaps the Waldorf Cafeteria, a famous New York hangout where the Abstract Expressionists congregated for cheap coffee before moving on to the Cedar Bar? In his 1971 poem “from all these, you,” Harold Norse (who knew Burroughs) wrote of “the Waldorf Cafeteria where we dunked pound cake in coffee till 5 a.m. with nowhere to go.” Was Norse writing about a common experience, i.e. hanging out at the Waldorf Cafeteria, or was he riffing on Naked Lunch?

Certainly Burroughs knew of the Waldorf Cafeteria, located in Greenwich Village just off the intersection of 8th Street and 6th Avenue (currently the site of a Staples office supply store). The place is mentioned in one of Jack Kerouac’s chapters in And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks — “they had just had a cup of coffee at the Waldorf Cafeteria…” Conversely, Naked Lunch refers to a Waldorf, while those speaking of the Village hangout typically referred to the Waldorf. To make matters even more confusing, in The Job Burroughs situates a Waldorf Cafeteria in St. Louis — “It was a hot June day in St. Louis day like any other breakfast at the Waldorf Cafeteria bacon eggs toast and coffee…” Fiction? Ambiguity? Doppelgänger lunchrooms proliferating in Burroughs’ overheated imagination?

Bickford’s

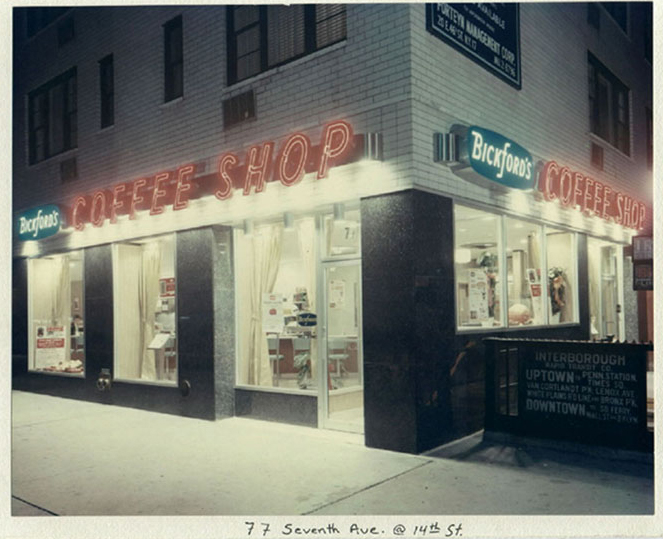

Another place to dunk pound cake was Bickford’s cafeteria, a popular chain in New York until it sputtered out in the 1960s. The place was well known for cheesecake, apple pie, rice pudding — and for tolerating those who spent less time eating than meeting. In her memoir You’ll Be Okay: My Life with Jack Kerouac, Edie Kerouac Parker wrote that “Jack and Bill would hang out having coffee at Bickford’s, discussing anything and everything.” Burroughs wrote: “not only did they have very good food, excellent food and very cheap, but also they were all meeting places, drug meeting places… The 42nd St. Bickford’s was a notorious hang-out for thieves and pimps and whores and fags and dope pushers and buyers and everything.” (Quoted in Bill Morgan, The Beat Generation in New York) Doubtless it was less the diners than the malingerers whom Allen Ginsberg had in mind when he wrote in “Howl” that they “sank all night in submarine light of Bickford’s.”

In Junky, Lee makes use not of the Times Square Bickford’s but of another location downtown. Preparing to sell heroin to a kid named Chris, Lee makes a “meet with him for the next day in the Washington Square Bickford’s.” According to a listing of the locations in New York, there never was a Bickford’s at Washington Square proper. A reference to “Bickford’s Cafeteria near Washington Square” appears in a life of the logician Alfred Tarski, which suggests that it may have been a matter of a nearby Bickford’s — likely the one situated at the corner of 7th Avenue and 14th Street. It is also possible that in Junky Burroughs fabricated the existence of the Washington Square branch, though most of the other locations mentioned in the book were real enough.

In a passage deleted from the “restored” edition of Naked Lunch, Burroughs had written: “The living and the dead… in sickness or on the nod… hooked or kicked or hooked again… come in on the junk beam and The Connection is eating Chop Suey on Dolores Street… dunking pound cake in Bickfords… chased up Exchange Place by a baying pack of people.” Apparently the passage was excised because it echoed one that appears earlier in the book: “The living and the dead, in sickness or on the nod, hooked or kicked or hooked again, come in on the junk beam and the Connection is eating Chop Suey on Dolores Street, Mexico D.F., dunking pound cake in the automat, chased up Exchange Place by a baying pack of People.” That the passages repeat one another may be less significant than that they differ in small ways. Burroughs transposes Bickford’s with the automat, creating an equivalence that is reinforced by the fact that “dunking pound cake” occurs in all three places — the Waldorf, Bickford’s, and the Automat. It’s as though they shlup together into a single anonymous eatery, the Meet Cafe as meta-cafeteria.

The Automat

To the Burroughs who lived in New York in the early 1940s, the Automat must have been something like what Starbucks is to New Yorkers today. Locations were ubiquitous — in 1941, 157 Automats in Philadelphia and New York were serving half a million customers per day — and it was a good place to sit if you didn’t want to be hurried. The Automat was known not just for quality food (macaroni and cheese, baked beans, creamed spinach, fish cakes) but for the coin-operated vending machines that dispensed the stuff. You get a whiff of the place in Hippos, where Burroughs wrote, “We left the bar and went over to the Automat on 57th Street and each had a little pot of baked beans with a strip of bacon on top.”

After Hippos, however, it is no longer the food that makes the Automat noteworthy. Junky: “We had a cup of coffee at the 34th Street automat and split the last take. It was three dollars.” Although you could write a fabulous dissertation on the role played in Naked Lunch by acts of eating (which include cannibalism and coprophagia), the irony is that little eating gets done at the Waldorf, Bickford’s, or the Automat. “Dunking pound cake” is less a matter of satisfying hunger than of waiting on the man. It’s a mechanical gesture, repeated while killing the endless hours before the Connection or the dealer appears with his dope. In “The Junky’s Christmas,” a story which dates from the early 1950s, Danny the Car Wiper “stopped in the Automat and stole a teaspoon” — not to eat with, obviously, but to cook up with.

To track the Automat from Hippos to Naked Lunch and beyond is to observe a process like the one that occurs to the addict whose flesh falls off him when he shoots up. You get the sense that it’s a real New York place, then the eating gives way to dealing, and then the dealing gives way to something else. “The Rube flips in the end, running through empty automats and subway stations, screaming: ‘Come back, kid!! Come back!’” What are those empty Automats? Real places? Locations in a novel? Poetic figures? Fading memories in the mind of an expatriate heroin addict? By the time Burroughs writes of the Automat in Nova Express, it has completed a process of derealization:

I cut into the Automat and put coins into the fish cake slot and then I really see it: Chinese partisans and well armed with vibrating static and image guns. So I throw down the fish cakes with tomato sauce and make it back to the office…

Many an Automat served up fish cakes, but none on earth were armed with vibrating static and image guns. The Automats in New York slowly closed up, emptied by suburbanization and the rise of fast-food restaurants, but clearly they left some outposts in the imagination of William S. Burroughs.

(Text: Supervert)